What a Great Question! Cultivating Curiosity in Montessori

Some photos in this post were taken before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some photos in this post were taken before the COVID-19 pandemic.

I think, at a child's birth, if a mother could ask a fairy godmother [for] the most useful gift, that gift would be curiosity. Eleanor Roosevelt

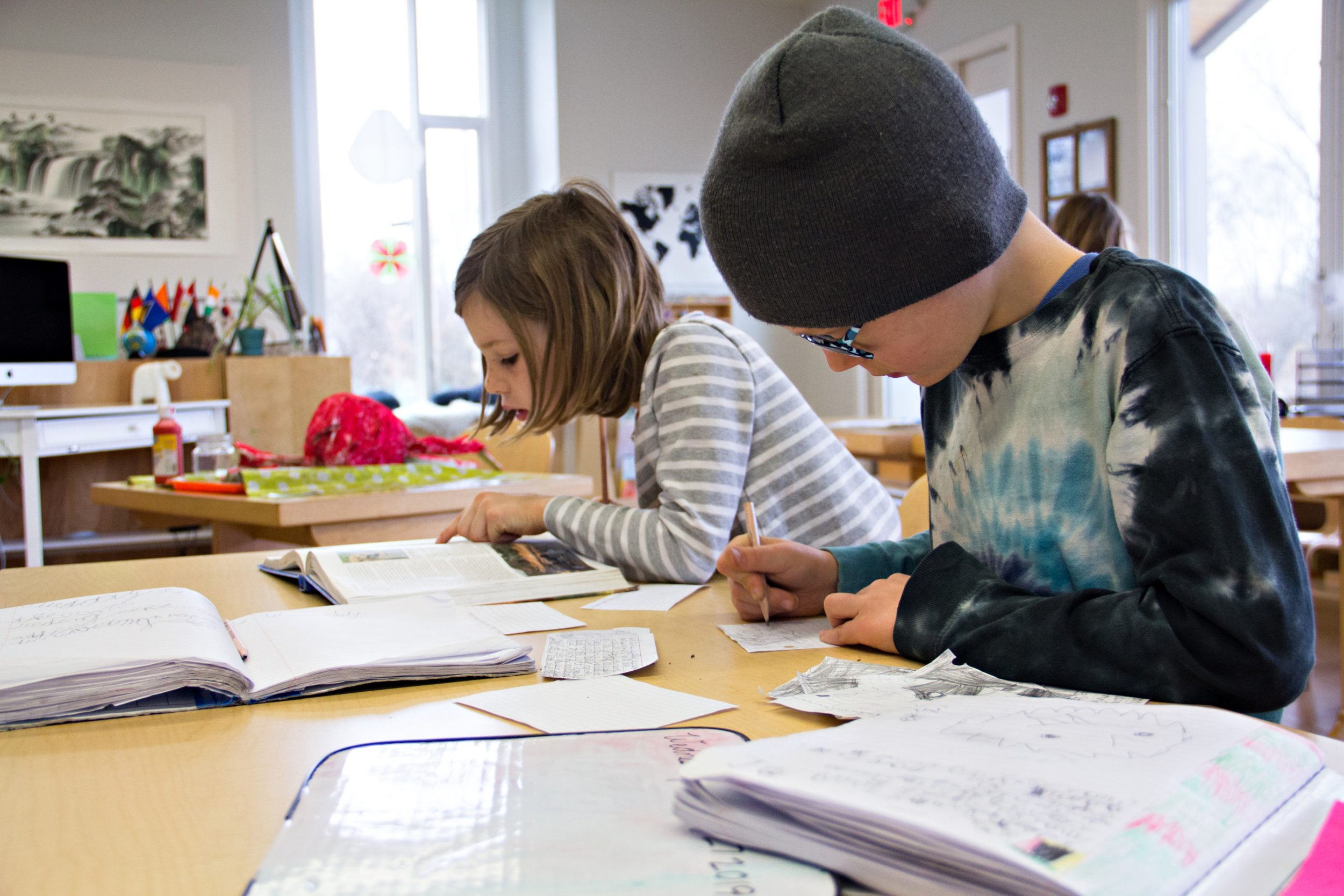

Over the years, our guides have hosted numerous on-campus events to deepen our community's understanding of Montessori and how we implement it here at Villa di Maria. As a parent and a staff member I've attended quite a few of these events and I can honestly say that each and every one has reinforced my appreciation for our guides' and assistants' dedication to our students.I could write an entire post gushing about the wisdom our guides share at each of these events, but that is a topic for another day. Today I want to share something from the events that has especially resonated with me because it so simply and precisely sums up one of the most important principles of a Montessori education: the cultivation of a lifelong love of learning through the encouragement and promotion of the child's innate curiosity. This topic comes up regularly at events, in conversations about what sets Montessori apart from traditional methods of education. And the best summary of it I've heard was given by Upper Elementary Guide Rebecca Callendar when she said that her favorite way to meet her students' questions is with... What a great question!  This response, as simple as it seems, is really quite powerful. If you've spent any time with children, you know that they are dedicated, persistent (sometimes relentless) question-askers. The sky, their breakfast, the neighbor's car, the leaves on the trees, the street lights, the huge eyebrows on that man at the grocery store... nothing is spared the curiosity of children. They will ask questions about all of it. All. Of. It.When they are very young, children are taking in everything around them—collecting endless data from their surroundings. They begin to store, categorize, quantify and sort that data, to process the world with countless repetitions of who?, what?, when?, where? and, of course, WHY?

This response, as simple as it seems, is really quite powerful. If you've spent any time with children, you know that they are dedicated, persistent (sometimes relentless) question-askers. The sky, their breakfast, the neighbor's car, the leaves on the trees, the street lights, the huge eyebrows on that man at the grocery store... nothing is spared the curiosity of children. They will ask questions about all of it. All. Of. It.When they are very young, children are taking in everything around them—collecting endless data from their surroundings. They begin to store, categorize, quantify and sort that data, to process the world with countless repetitions of who?, what?, when?, where? and, of course, WHY?

As they get older, their questions increase and become more complicated as they begin to use their reasoning minds and develop their imaginations—as they begin to practice abstract thought.Asking questions is the primary method children use to learn. So when adults meet their questions with statements like What a great question!, we are sending a powerful message. Multiple powerful messages, in fact. We are teaching children that they are allowed to actively participate, and even take control, in their learning; that their curiosity, their drive to know more and more about the world, is a positive (a great!) thing; and that their voice matters and is being heard.And that's not all! In addition to the confidence-promoting benefits listed above, there's something else happening, something a bit more... strategic. When we say, What a great question!, we are actually withholding an answer. Think back again to any time you've spent with any child, to when those questions started flowing. The easiest thing to do would be to just answer. Or to change the subject or invoke the quiet game. But ending a question with an answer or a redirect puts a stop to the learning.Of course there are some questions that call for simple answers, but I would go out on a limb to say that most questions being asked by a child aren't simple. Most questions are an indication that synapses are firing, that intellectual curiosity is at work, that discovery is happening, that we are in a moment when the child is inspired and motivated to learn.

As they get older, their questions increase and become more complicated as they begin to use their reasoning minds and develop their imaginations—as they begin to practice abstract thought.Asking questions is the primary method children use to learn. So when adults meet their questions with statements like What a great question!, we are sending a powerful message. Multiple powerful messages, in fact. We are teaching children that they are allowed to actively participate, and even take control, in their learning; that their curiosity, their drive to know more and more about the world, is a positive (a great!) thing; and that their voice matters and is being heard.And that's not all! In addition to the confidence-promoting benefits listed above, there's something else happening, something a bit more... strategic. When we say, What a great question!, we are actually withholding an answer. Think back again to any time you've spent with any child, to when those questions started flowing. The easiest thing to do would be to just answer. Or to change the subject or invoke the quiet game. But ending a question with an answer or a redirect puts a stop to the learning.Of course there are some questions that call for simple answers, but I would go out on a limb to say that most questions being asked by a child aren't simple. Most questions are an indication that synapses are firing, that intellectual curiosity is at work, that discovery is happening, that we are in a moment when the child is inspired and motivated to learn.

It's not that I'm so smart, it's just that I stay with problems longer. Albert Einstein

What a great question! seizes that moment of inspiration and motivation and turns into an opportunity for deeper learning. What a great question! isn't the end of the conversation. It's the beginning. It is followed by any number of prompts to further engage the child in learning. The guide might suggest the child seek out a friend to discuss the question; she might offer a list of resources for the child to explore and find answers; she might suggest a research project or report; or she might guide the child toward more questions, toward a deeper exploration. Because here's the strategy: the ultimate goal of the guide in a Montessori environment is not to fill a child's head with answers and facts. The ultimate goal is to foster a true, lifelong ability to learn.

Higher Order Thinking and Metacognition

Higher Order Thinking and Metacognition

As academic as these concepts might sound, higher order thinking and metacognition are routine practices that most of us engage in every day. If you've been to a book club, deliberated over a large purchase or argued over politics, you've engaged in higher order thinking. And if you've ever thought about what you're thinking—if you've caught yourself being distracted or questioned your own thoughts on something—that's metacognition. I've included some resources at the bottom of this post if you want to read more about these concepts and their more formal applications in the field of education.Higher order thinking is the thinking we do that goes beyond memorization and recollection of facts. It's the deeper cognitive processing that happens when we analyze, evaluate, compare, contrast, synthesize information, think critically, think creatively, use metaphors and analogies, make inferences, express opinions, make judgments and engage in what-if thinking.Strictly speaking, metacognition is a form of higher order thinking. I'm giving it its own spotlight here because it carries with it something I believe the world could use a little more of these days. Research shows that when we think about our own thinking, we become more self-aware and possibly more empathetic. So, higher order thinking, including metacognition, is the ultimate goal for the Montessori-educated child. But why? It is the kind of thinking that's more complex, requires more concentration, more time, more work. It is, frankly, harder. And it also the kind of thinking that inspires deeper research and encourages students to explore. It fosters creativity and leads to discoveries. It helps children navigate difficult social situations and develops empathy. It has been shown to strengthen the brain by creating new synapses. And most importantly it instills in children a confidence in their own intellect. It gives them a true love of learning.

So, higher order thinking, including metacognition, is the ultimate goal for the Montessori-educated child. But why? It is the kind of thinking that's more complex, requires more concentration, more time, more work. It is, frankly, harder. And it also the kind of thinking that inspires deeper research and encourages students to explore. It fosters creativity and leads to discoveries. It helps children navigate difficult social situations and develops empathy. It has been shown to strengthen the brain by creating new synapses. And most importantly it instills in children a confidence in their own intellect. It gives them a true love of learning. And it all starts with something that children bring with them naturally—an endless, wonder-filled curiosity.

And it all starts with something that children bring with them naturally—an endless, wonder-filled curiosity.

References and Additional Resources

- The Absorbent Mind by Dr. Maria Montessori

- Child categorization

- Children's questions: a mechanism for cognitive development

- A Focus on Critical Thinking

- Found ways to help students answer their own questions

- Helping Students Ask Better Questions by Creating a Culture of Inquiry

- Higher Order Thinking

- How Parents Can Teach Kids Critical Thinking

- How to Lead Students to Engage in Higher Order Thinking

- What Is Metacognition? How Does It Help Us Think?

- When children ask questions, they are learning how to solve problems

Photos courtesy of Melinda Smith and Melissa LeBeau.